Tracking Your Browser Fingerprint

Most of us understand that we are being tracked on the web, and most of us understand the basics of cookies. However, this is not the whole picture. While cookies track you as you traverse the web, fingerprints attempt to identify you without tracking. Here, I will attempt to give a basic overview of how fingerprints are created, and how to protect yourself from being identified.

Creating a fingerprint

A fingerprint does not necessarily use cookies. In fact, fingerprinting exists to get around cookie blockers. Ad companies always want to identify you, even if you are blocking their cookies. Instead, a website looks at your browser environment.

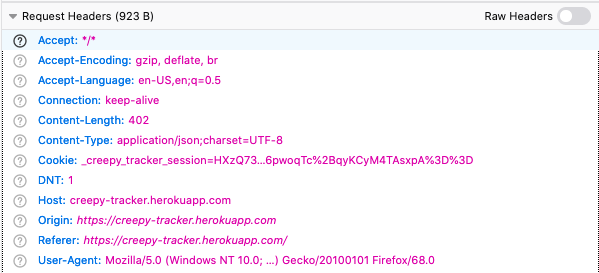

Let’s start simple. Your user-agent header is present in every request. For example, in Chrome, mine is: Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_15_4) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/81.0.4044.138 Safari/537.36. In Firefox, mine is: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; rv:68.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/68.0. Notice that for each value, there is also a version number. Thus, you can break your users down by their browser and version number. There are even more headers that will be sent with each request (shown are my Firefox values):

|

|---|

| Some headers in Firefox |

Much like describing a person, the more information you get, the more likely you are to uniquely identify your visitors. You can first put people into broad categories: what color is their hair? However, the more categories you add (height, weight, skin tone, shoe size, age, city they live in), the more likely that you are describing a unique individual.

|

|---|

| Blondes, brunettes, or redheads? |

Headers are not enough

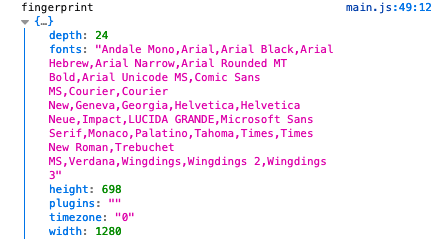

If you check your browser headers, you will notice that there are only a few. Additionally, most of these aren’t very descriptive. To get more information about your browser environment, we can use Javascript. To correctly render the page, Javascript and CSS need to know many things about your browser environment. For example, we can get the screen resolution (screen.width, screen.height), we can get your time zone (new Date().getTimezoneOffset()), as well as more complicated things. At this point, the only real limit is creativity.

|

|---|

| Some values that JS can access |

Note that plugins is empty in Firefox. In my Chrome, however: "Chrome PDF Plugin; Portable Document Format; internal-pdf-viewer; ,Chrome PDF Viewer; ; mhjfbmdgcfjbbpaeojofohoefgiehjai; ,Native Client; ; internal-nacl-plugin; ".

Going even further, there are websites devoted entirely to how much information can be received from your browser.

Some privacy measures make you more noticeable

While some features help protect you against trackers, they will conversely make you easier to fingerprint.

“More subtly, browsers with a Flash blocking add-on installed show Flash in the plugins list, but fail to obtain a list of system fonts via Flash, thereby creating a distinctive fingerprint”

However, Nikiforakiset et al. showed that they may be harmful as they found that these extensions “did not account for all possible ways of discovering the true identity of the browsers on which they are installed” and they actually make a user “more visible and more distinguishable from the rest of the users,who are using their browsers without modifications”

- Quoted from the FP-Stalker paper, the Nikiforakiset paper they are referring to is listed in the sources.

A Simple Implementation

I created a simple fingerprinting website myself. It is missing a few things (supercookies, all fonts, etc). After submitting it to my bootcamp’s Slack, I received:

Fingerprint.count: 68 fingerprints,User.count: ~100 users.

This means that I have several fingerprint collisions. I estimate that I uniquely identify two-thirds of my users, using only eight variables. Many major fingerprinters have 60+ variables.

Here are some more interesting stats I collected:

Fingerprint.where('lower(user_agent) LIKE ?', '%firefox%').count= 7Fingerprint.where('lower(user_agent) LIKE ?', '%chrome%').count= 46Fingerprint.where('lower(user_agent) LIKE ?', '%iphone%').count= 11Fingerprint.where('lower(user_agent) LIKE ?', '%android%').count= 1 (The remainder are likely safari on MacOS)

How to prevent?

If you want to prevent being fingerprinted, your goal is to not be unique. You should want a set up that is both:

- commonly used

- does not communicate much about you

Ideally, this will put you in a large Anonymity Set.

The Nuclear Option: Disable javascript

If you want to be hard to fingerprint, disabling javascript will prevent EVERYTHING stated above that is not a header. And since headers are limited, there is limited information that can be ascertained about you. The website can tell that you have disabled JS, but not much else.

Of course, this can come with its own set of problem. Javascript powers much of the internet, and will make many websites difficult to use. The simple fingerprinting website that I set up will not even run at all! - But don’t take that as a good example.

Anti-fingerprinting browsers

Tor is the best example of this. While not perfect, Tor has many in-built methods to block fingerprinting. Some fields are written to be as general as possible, others are randomized to each website that requests them. Of course, Tor is incredibly slow, and makes it difficult to browse the internet.

Along a similar line, Firefox has an in-beta anti-fingerprinting tool, and prevents access to some Javascript functions used by fingerprinters.

For mobile, iPhone is much better than Android (unsurprisingly). However, the majority of data I have on mobile browsers is ~10 years old, and therefore difficult to be sure about.

|

|---|

| I don’t recommend using the browser made by the advertising company |

Attempt to become average

You want as many of your environment variables to be average, and you can set many of these. For example, you can fix the size of your screen to 1366x768, or set your time zone to a high-population area.

Fingerprinting Bad

You may be reading this and think that I have an overwhelmingly negative association with browser fingerprinting. Well, yes, I do. It allows advertisers to uniquely identify you.

Still, there are some cases where fingerprinting has a valid use case. For instance, in fraud detection. An excellent article was recently posted to HackerNews about eBay checking user ports. A few users pointed out that this can be useful in fraud detection. If fraudsters overwhelmingly carry similar fingerprints, it may be useful to identify visitor fingerprints. Of course, this is a narrow use case, but it does exist.

In Conclusion

- Your fingerprint is inferred by your browser environment variables

- Javascript is needed to access most of these

- Try to be boring

Like this post? You can also give it some claps on Medium.

Further Reading & Sources

- Slido Medium Article

- How Unique is Your Browser? - A whitepaper by EFF.

- Panopticlick - EFF will show your fingerprint to you

- BrowserSpy - various methods for retrieving browser information

- FingerprintJS2 - A more up-to-date fingerprinting resource

- Am I Unique - illustrates a very up-to-date view of your fingerprint

- N. Nikiforakis, A. Kapravelos, W. Joosen, C. Kruegel, F. Piessens, andG. Vigna, “Cookieless monster: Exploring the ecosystem of web-baseddevice fingerprinting,”Proceedings - IEEE Symposium on Security andPrivacy, pp. 541–555, 2013.